The City of Victoria and local police are stepping up in the battle against drug-fuelled street disorder and violence in the downtown core, say local business leaders.

Now it’s the province’s turn.

“We are very pleased that the city has made some tough decisions, some bold decisions, and taken money from other areas that maybe were a priority a year or two ago, and recognizing that this is a priority,” Jeff Bray, CEO of the Downtown Victoria Business Association, says of the city’s sudden $10.35-million reallocation of funds in early July to tackle rising street disorder downtown.

“We would like to see the province move equally quickly and equally boldly to start delivering the services that they need to do to make the big difference overall here. The city’s doing what they can, doing more than they should in the absence of the province. Now’s the time for the province to match that.”

That funding announcement — which included new money to hire an additional 12 bylaw staff as well as funds for nine new or redeployed police officers to focus on the troubled Pandora and Princess avenues — came as a result of escalating public concern over homelessness, open drug use and violence throughout the downtown of the provincial capital. Bray’s DVBA sent shock waves through the city in early June with its annual report — subtitled “A Wake Up Call” — and attached a survey of its members on the state of the city’s downtown, where homelessness and addiction have become public spectacles in the last few years. That was quickly followed by the release of the City of Victoria’s own Community Safety and Wellbeing Plan, a culmination of two years of work that includes dozens of recommendations for all levels of government to address the crisis.

But what really got the $10.35 million suddenly on the table was an eruption of violence at the end of June. Among the incidents: Yates Street bike shop owner Tyson Schley suffered a broken arm after being attacked by a man while trying to close his business for the day. He remarked in a Facebook post afterwards that “the growing lawlessness downtown is impossible to ignore and incidents like this are becoming far too common.” He also called for “bold action, not more reports or empty promises” from all levels of government.

“In the short term, enforcement will make a big difference,” Bray says of the city’s and its police department’s moves to enforce existing bylaws. “But without the province stepping up and delivering the variety of services some of these individuals clearly need, whether that’s jail time or mental health and addiction services, it’s not going to have a lasting effect.”

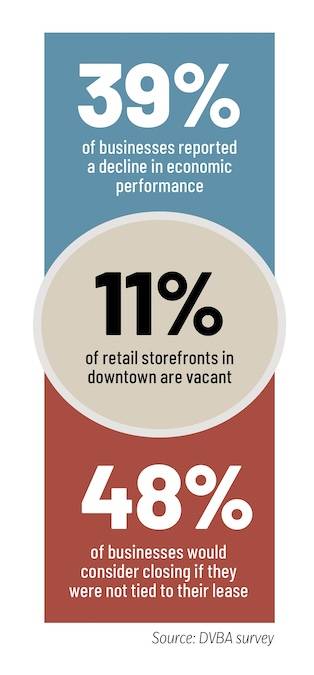

The DVBA’s survey of its members, included in its report, points to the potential perils of not addressing the issue. Among its findings, 39 per cent of businesses reported a decline in economic performance in the downtown area with a business vacancy rate of 11 per cent. Moreover, when asked if their lease was ending and whether they’d renew it based on current conditions downtown, 48 per cent of businesses surveyed said they would not, or weren’t sure.

Thirty-plus per cent of the DVBA’s 1,800 membership took part in the survey, says Bray.

“We are at that tipping point, because once people say, ‘we’re out,’ it will be almost impossible to convince them otherwise,” he says. “If they’re on the fence, they’re looking for that thing that says, OK, I can have more confidence.’ ”

That means getting all levels of government involved. While the city addresses immediate concerns like enforcing existing laws on drug use in public or continually sheltering in public spaces, provincial and federal levels of government are tasked with longer-term solutions like health care, housing and criminal justice reforms.

“I’m hoping that the province, quite frankly, is a little embarrassed because if you look at the [recommendations] in the city’s Community Safety and Wellbeing Plan, almost half of those are really provincial responsibilities, but the city is saying we can’t wait so we’re going to get on with it,” says Bray.

“My hope is the province realizes that it’s not a good look for cities to be looking at health care and some of these other things that are really provincial responsibility, so they step up and get the health authority to quickly start contracting out the appropriate services that meet the needs of the individuals, but also meet the needs of the community.”