In Phillips Arm, a mainland inlet about 50 kilometres north of Campbell River in Kwiakah First Nation territory, an old fish farm has found new life. The farm’s floating infrastructure has been transformed into a base for Kwiakah’s Guardian program and a trial seaweed program.

The idea for growing seaweed here came from an aquaculture paper that caught the attention of Frank Voelker, Kwiakah band manager and economic development officer. The paper introduced him to multi-trophic aquaculture — a method where species like kelp, oysters, sea cucumbers and sablefish are cultivated together, each benefiting the next all while improving the ecosystem.

It’s an approach to aquaculture that not only produces sustainable food, but could also help restore the environment. It’s also an approach that aligns with millennia of First Nations’ traditions and generations of expertise. Now, more and more of them are looking to a future of growing and harvesting kelp.

Learning from Experience

According to Statistics Canada, aquaculture contributed just over $916,000 to British Columbia’s economy in 2022 (the most recent year for which figures are available). Although it represents a small portion of the total fishery, the sector — including shellfish and seaweed — has shown steady growth in both production and commercial value.

One of the biggest draws of this type of aquaculture, particularly for First Nations, is its low environmental impact. Shellfish cultivation thrives in clean water, requires no added feed or chemicals and produces little waste — all positives for marine ecosystems. Meanwhile, seaweed, a growing global market currently valued at US$6 billion, not only creates ocean habitats and shows potential for carbon sequestration, it’s also becoming a valuable food source and may even replace fossil fuels in fabrics and plastics. Intrigued by all these potential benefits, Voelker brought the seaweed farm proposal to Kwiakah’s chief and council. “I found it exciting because there are no inputs needed. You put the seeds in the sea, and the water and sunlight do the work,” he says. “It’s not like traditional agriculture, where you harm your soil with fertilizers, pesticides and herbicides. And you’re not really a farmer — you’re more of an observer and then a harvester.”

For the Kwiakah, whose membership recently affirmed conservation as a guiding principle in their Nation’s constitution, seaweed farming seemed to align with their vision of building a sustainable economy that could also help restore their territory. “There’s been significant industrial activity in Kwiakah territory over the years,” Voelker says. “We don’t even know the full extent of the damage.”

While seaweed farming — and the broader plan to gradually integrate other species — seemed promising on paper, Kwiakah’s elders chose a cautious, science- based approach. “We can’t make decisions about development without research,” Voelker says.

“There are no inputs needed. You put the seeds in the sea, and the water and sunlight do the work.” — Frank Voelker

Their caution was informed by past experiences with salmon farming. At its peak, that industry employed 700 Indigenous people and provided $120 million in annual economic benefits to First Nations. As it expanded, some of Kwiakah’s neighbouring Nations embraced it as an economic opportunity. However, the Kwiakah resisted, demanding more scientific data. “We faced pushback from the government and fish-farm companies,” Voelker recalls. “As a small Nation, they didn’t see us as important enough to engage with.”

Undeterred, the Kwiakah invested in an independent study of the farms in their territory. “One hundred per cent of the fish tested were infected with piscine reovirus,” Voelker remembers. “This was on top of issues with amoebic gill disease.” Though the results were distressing, the knowledge came with a silver lining. The fish-farm operator that had set up shop in Kwiakah’s traditional territory agreed to withdraw. To compensate the Nation for their multi-year tenure, they left behind the fish farm — the docks, float houses and sheds stayed anchored in place.

A Collaborative Approach

Determined to find up-to-date scientific data about the risks and benefits of growing kelp, the Kwiakah First Nation turned to community experts. One collaboration was with North Island College’s (NIC) Centre for Applied Research, Technology and Innovation (CARTI). Naomi Tabata, CARTI manager at NIC, says that NIC has provided expert help and resources to a number of aquaculture businesses by offering applied research partnerships. “Aquaculture is an important part of local communities and to Canada’s sustainable food production, but growers have a number of questions and face a variety of challenges,” says Tabata. “These collaborations help address some of these challenges by combining our expertise at the college with that of the Nations.” As the Kwiakah were deciding which questions they had, a new challenge arose — wild kelp harvesters had begun popping up in the territory with government-issued licences. “From talking to the elders, I knew industrial activity had already put pressure on the wild kelp, and it wasn’t as abundant as it once was,” Voelker says. “The government was allowing the harvesters to take 20 per cent, but how do you accurately determine that? And how do we know that 20 is the magically sustainable percentage?”

The Nation’s first step in collaborative research was mapping the distribution and biomass of wild kelp beds along their rocky shores. After an aerial survey in 2020, the team repeated the study in 2023, adding scuba dives to gather underwater data.

Meanwhile, logistical questions emerged about the economic viability of kelp farming in such a remote location. “Our farm is about 70 kilometres from the nearest processing facility and transporting cultivated kelp would be costly — it’s essentially like shipping water,” Voelker notes. He also questioned the practicality of the potential solution of having each Nation process and market its own seaweed products.

As the aquaculture plan stalled, the Kwiakah realized that their focus on traditional stewardship, backed by science, was leading them toward a broader vision: a conservation-based economy. They had the perfect resource in the former fish farm, which could serve as a research site for studying kelp cultivation, carbon sequestration and the ecosystem impacts of seaweed farming. It could also house their regenerative forestry pilot program.

So the new Kwiakah Centre for Excellence was born. Opening in spring 2025, the floating facility will have accommodations and amenities to support up to 16 scientists and stewardship staff. “Someone has to look out for the environment, or it gets pushed aside,” says Voelker.

Connection to Land and Sea

Science has always been part of Indigenous aquaculture and stewardship practices. In the past, rather than partnering with research institutes like CARTI, coastal Nations relied on generations of observations. This deep connection to their territories enabled Indigenous Peoples to develop aquaculture technologies such as terraced clam gardens, which boosted butter clam yields by up to four times, as well as fish traps and weirs that were designed to carefully manage fish harvests.

As the land’s guardians, they also held a sacred responsibility not just to keep their people fed through harvests and trade agreements, but to keep their territories healthy and in balance.

In 2023, Cascadia reported that the 20 kilometres of kelp production line planted off Diplock Island in Barkley Sound was their most productive site, producing over 75 tonnes of kelp.

This is why several Nations are investing in businesses that blend stewardship with economic success. Among them are the Klahoose, who are working on kelp farming and run a geoduck nursery; the K’ómoks, who own Pentlatch Seafoods and farm oysters and clams while exploring options for abalone, scallops, geoduck, cockles and mussels; and the T’Sou-ke, who recently converted their oyster barge to solar power.

They know that in the long run, people can’t thrive without a healthy environment. Oral teachings that detail other ancient aquaculture practices — including herring egg gardens, where kelp fronds or tree boughs were placed in bays to catch herring spawn, and estuary gardens, where perennial root gardens were built in coastal estuaries — reinforce this principle: Caring for the environment ensures that the environment, in turn, takes care of you.

Many Nations have started investing in aquaculture, but a key challenge is that most territories have suffered significant ecological damage. The 19th-century sea otter hunt and later the logging industry destroyed the vast kelp forests in Barclay Sound, says Larry Johnson, president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Seafood Limited Partnership (NSLP), a sustainable seafood business owned by six partner Nations — Ditidaht First Nation, Huu-ay-aht First Nations, Uchucklesaht Tribe Government, Ucluelet First Nation Government, Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation and Ka:’yu:’k’t’h’/Che:k’tles7et’h’ First Nations — on the Island’s west coast. When the kelp disappeared, the nurseries and habitat for small fish such as herring, salmon and rockfish were also damaged. So Johnson says the first step of building a seaweed farm was planting enough to help the environment.

While the effort to help an ecosystem recover in tandem with developing a business can seem like a slow way to become successful, Johnson points out that it reflects a different world view — one rooted in interconnectedness. “By putting back something that’s been missing, we make the system healthier.” While the initial investment may cost more and take longer, Johnson argues that it leads to greater abundance — and profits — in the long run.

Growing Resilience

With seaweed cultivation, Johnson says, it’s the exciting unknowns that intrigue him most. “We already know we can make biodegradable plastics like grocery bags, get carrageenan for foods and cosmetics and that kelp may help slow down climate change, but the technology is just starting. We don’t know what might be next.”

This is why partnerships with experts like CARTI and Cascadia Seaweed are such an important step, he says: “We’re able to get guidance and support while sharing our knowledge and offering research opportunities to scientists.” Johnson sees NSLP’s path forward as one that’s more co-operative and less competitive.

“Traditionally, that’s the way we were. We didn’t value the things we had by hoarding them for ourselves. We show something’s value by sharing it with the world,” he says. While NSLP’s kelp-farming partnership with Cascadia Seaweed is still new, the enterprise is already finding success.

In 2023, Cascadia reported that the 20 kilometres of kelp production line planted off Diplock Island in Barkley Sound was their most productive site, producing over 75 tonnes of kelp. After harvest, the crop was processed into a liquid plant food for home and garden plants at a facility in Port Alberni.

As the Kwiakah First Nation, NSLP and other Indigenous communities in British Columbia forge ahead with these new forms of aquaculture, their efforts are rooted in both innovation and tradition.

By combining cutting-edge science with deep respect for the land and sea, they are healing ecosystems damaged by industrial activity while also creating sustainable economic opportunities.

Seaweed and shellfish farming represents more than money making — it’s a way to restore balance and foster resilience for future generations. Through cautious, deliberate stewardship, these Nations are paving the way for a new model of economic growth — one where environmental health is as valued as economic success.

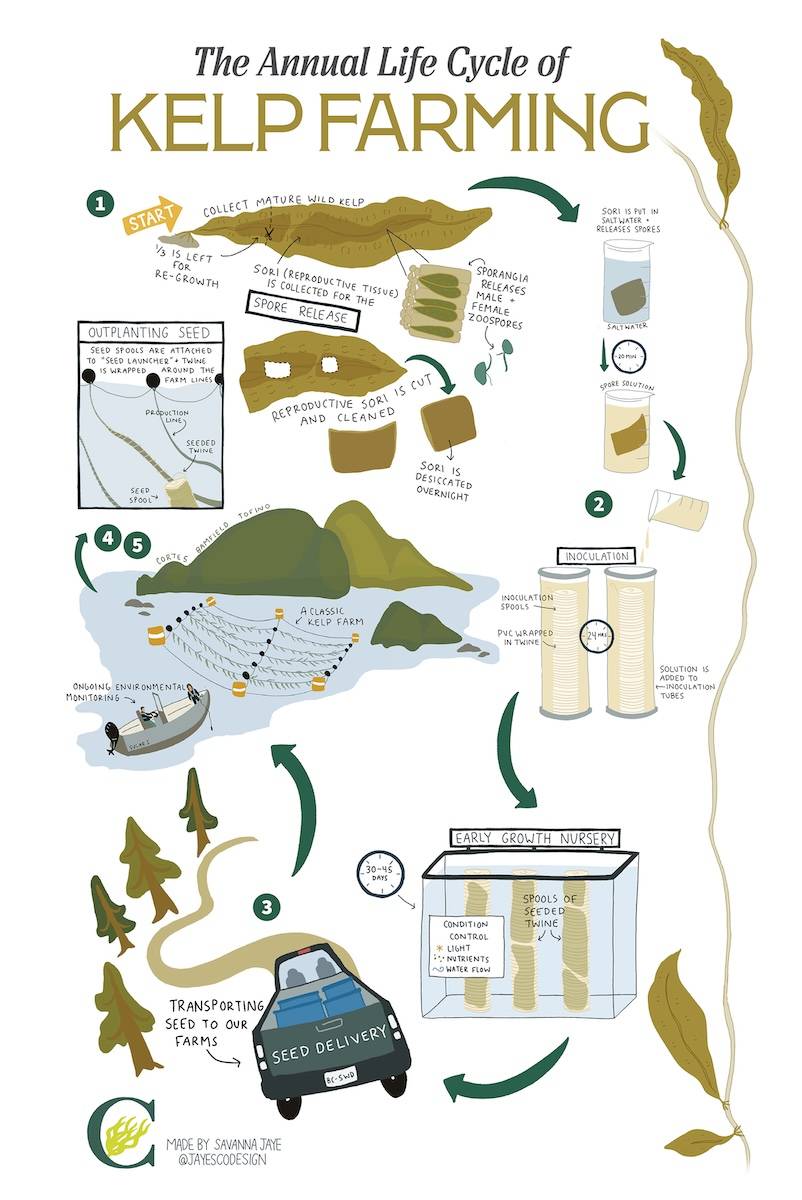

The Annual Life Cycle of Kelp Farming

The cooler months of the year are the busy season for seaweed farming on this coast; here’s how the annual cycle of kelp farming breaks down:

October

October

- Farmers collect sori, the mature kelp with reproductive tissue, from the wild and transport it to a kelp hatchery.

- Reproductive tissues are stimulated to release spores, which then settle on spools of twine or rope in inoculation tubes at the hatchery.

- This is also time to rehab any gear (such as anchors, ropes or floats) that might need it.

November

- More spores are released and spools of twine inoculated. New farms may be built.

- Environmental monitoring of the sites is ongoing.

December

- Seed is outplanted — spools of seeded twine are trucked from the plant to the farm, where they are attached to the lines on site.

- Growth of the kelp is closely monitored. Environmental monitoring continues.

January and February

- Kelp grows rapidly during the cooler months, reaching up to 15 feet or more in length.

- Farmers regularly visit the farm sites and closely monitor the growth of the kelp.

- Environmental monitoring also continues.

March and April

- Harvest typically occurs in spring, before waters warm up and “biofouling” (the growth of other organisms on the kelp) becomes a concern.

- Some kelp farms may trim the seaweed and allow it to grow back for a second harvest. The harvested seaweed is transformed into products such as food, pharmaceuticals and, most of all, a liquid seaweed extract used as a powerful plant food.

- Kelp growth slows down as water temperature rises; summer is the time for farmers to start planning for the next season.