When viewing Earth from space, it’s clear why it’s called the “blue planet.” What’s remarkable is that we know more about the surface of the moon than we do about our own oceans, with a mere five per cent of them having been explored by humans.

But a number of local businesses are changing that. With an established maritime industry, ocean-oriented research institutions and a collegial “let’s work together” attitude, it’s not surprising that Vancouver Island businesses are poised to take on what the United Nations calls the blue economy.

As defined by the UN, the blue economy comprises industries and policies that look to understand how we can sustainably manage our use of the ocean, while still using it as a tool for economic growth. And there is economic growth to be had.

“The global ocean opportunity is expected to grow to $3 trillion by 2030, doubling in size and outpacing the growth of the broader economy by close to 20 per cent,” says Kendra MacDonald, CEO of Canada’s Ocean Supercluster.

Although traditional industries will also benefit from the blue economy — from fisheries and aquaculture to shipping and offshore oil and gas — their success will depend on our understanding of the ocean ecosystems and how our activities affect it.

Many of the companies enabling that understanding are on Vancouver Island. Local ocean tech entrepreneurs are developing and deploying solutions to collect data and provide insights that will change how we view the sea around us.

Robot-Powered Rowboats

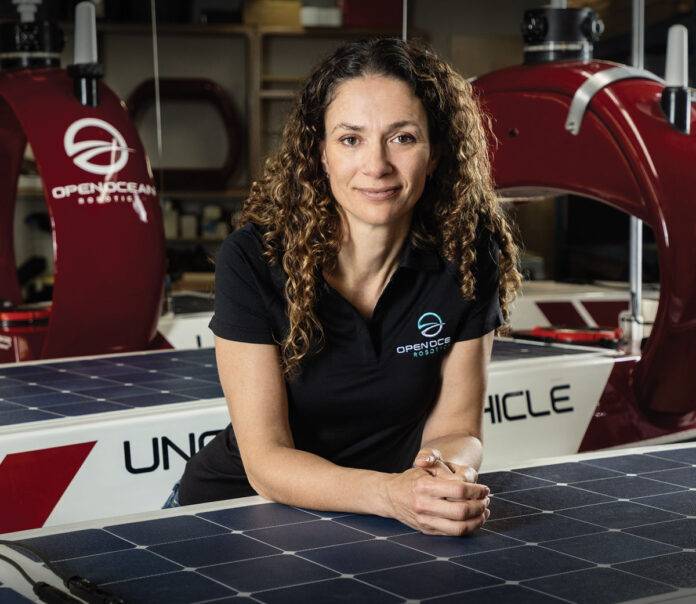

In 2005, Julie and Colin Angus rowed across the Atlantic Ocean, the first to successfully complete the passage from mainland to mainland. Along the way, they encountered two hurricanes, including Vince, which made an extremely rare landfall in Spain. It was while they braved the 50-foot waves that the idea for Open Ocean Robotics began.

If their rowboat could endure the ocean’s waves, they thought, so could robotic ones. And if those boats were solar-powered, they could stay at sea collecting ocean data for months, without emitting greenhouse gases.

In 2018, the Anguses launched Open Ocean Robotics. Now the company is practically a household name in the ocean tech sector. They have developed solar-powered, uncrewed surface vehicles (USVs) that can be deployed in challenging conditions for extended periods.

The three versions of the company’s USV, the DataXplorer, can be used to measure weather conditions, ocean currents and water depth and temperature. They can counter illegal fishing, map the seafloor and monitor marine mammals.

Open Ocean Robotics also provides a cloud-based platform, XplorerView MissionControl, that acts as a command and control centre for its USVs.

What’s in store for the future? “We’re now focused on commercialization,” says co-founder Julie Angus. “Our systems are very robust and we need to get them into the hands of customers.”

Finding Fish, Dodging Whales

Archipelago was founded in 1978 by a group of university biology graduates who were looking for a niche in marine-based environmental work. Years later, in the late 1980s, that niche became fisheries monitoring, which now represents nearly 90 per cent of Archipelago’s business.

Designed for harsh environments, the company’s on-vessel electronic monitoring systems collect data such as fish location, speed, vessel heading and various sensor readings. The data is loaded into FishVue Interpret, Archipelago’s analysis software, which uses AI to interpret the data and provide videos, maps and graphs.

For a niche application, Archipelago’s technology has a broad reach in its sector. President and CEO Gord Snell says that although there are fewer than 3,000 vessels carrying electronic monitoring equipment globally, Archipelago operates on nearly half of them.

South of the border in Washington state, 450 of Archipelago’s devices have been deployed on crab-fishing vessels to help regulators reduce interactions with whales. Using real-time maps and whale location patterns, regulators can make better decisions about when to close fishing areas.

Snell highlights such government regulations as a key driver for electronic monitoring demand.

“As more regions recognize the importance of sustainability in their fisheries, they need to find solutions to make that a reality, and electronic monitoring is one of them.”

In the meantime, Archipelago is full-speed ahead on hardware and software development, specifically AI-focused solutions. The company is partnering with Canada’s Ocean Supercluster, the National Research Council and the University of Victoria to develop cutting-edge AI tools that deliver even deeper insights.

Remotely Observant

Seamor Marine designs and develops remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) for underwater observation. Founded in 2006 by husband-and-wife team Inja Ma and Robin Li, the pair say that Seamor Marine is one of just a few companies in Canada exporting ROVs around the world and can be found on every continent and in every major body of water.

In Island waters, the ROVs provide an underwater window for marine researchers, conservationists, aquaculturists and infrastructure inspectors (think ports and pipelines). The technology allows them to gather data, monitor underwater structures and conduct maintenance — all without ever strapping on a dive suit.

One example is the recent use of a Seamor Chinook ROV, owned by the Penelakut First Nation, to survey marine ecosystems in its Gulf Islands territory. The ROV, equipped with a high-definition camera and multi-beam sonar system, was deployed to monitor the health of eelgrass, assess biodiversity and collect seabed data such as damage from freighter anchors. Ma and Li said that the alternatives — diving expeditions, towed cameras or ship-based surveys — would be costly, time-consuming and overall less effective.

Looking beyond the Island, the pair point to offshore oil and gas, scientific research, defence, renewable energy and underwater archeology as growth sectors for ROV tech.

Sensing Marine Safety

Founded in 2017, MarineLabs has a well-developed network of sensors on Canada’s Pacific and Atlantic coasts, as well as a test project with the U.S. Coast Guard in Connecticut. The sensors are rapidly deployable, self-contained, solar-powered and strapped onto buoys from which they send data to CoastAware, a cloud platform that customers access via subscription.

CoastAware collects real-time wind and wave data that is used by ports and pilots to safely operate and dock ships. In Canada and many other countries around the world, ports are legally required to have a vessel pilot bring every ship safely into port. The more information the vessel pilot is armed with, the better.

MarineLabs’ other customers are focused on climate resilience, a term becoming ever more popular as governments and politicians come to grips with what MarineLabs CEO Scott Beatty highlights as a multi-trillion-dollar problem.

“The thing that I’m continually reminded of, including by the latest climate events that we’ve all experienced, is that we have 100 years of emissions baked into our climate, and the effects of those haven’t been fully felt yet,” says Beatty. “If we stopped emitting all greenhouse gases immediately, we would still have 30 years of this to change.”

CoastAware provides climate resilience groups, such as coastal engineers, with historical data that can be used to predict weather patterns and help to plan marine infrastructure. Like many ocean tech companies, CoastAware uses AI to deliver insights, for example, the frequency and size of wakes from tankers passing the coastline.

Armed with a landmark $4.5 million in seed funding, the largest in Canadian ocean tech history, MarineLabs is now focused on growth. Beatty says the funding will be used to expand the company’s sensor network, add more team members and turn innovation into profit.

An Ocean’s Worth of Data

While it’s not an ocean technology company per se, it would be impossible not to mention Ocean Networks Canada. Established in 2007, ONC is a non-profit organization owned by the University of Victoria, with the simply stated but difficult-to-achieve goal of advancing our understanding of the sea.

The organization runs world-class observatories on all three Canadian coasts and in the Antarctic that deliver real-time data used freely by scientists and researchers, governments and industry. Building, maintaining and managing those observatories has given ONC essential insights into what works and what doesn’t when it comes to ocean tech.

One Island company benefiting from ONC’s experience is Rockland Scientific. Rockland provides sensors and software that measure turbulent flow in marine environments to help scientists better understand climate change. The company produces sensors designed for a variety of marine environments, including one compatible with Argo floats.

Argo floats drift freely through the sea at varying depths and are deployed in oceans around the world as part of an international ocean intelligence program. ONC uses Argo floats to monitor critical changes in ocean environments and is now working with Rockland Scientific to integrate the company’s sensors onto the floats and develop methods for data dissemination.

For ONC, the project increases the data that the Argo floats are able to collect. For Rockland, it expands a global market for its sensors.

In addition, ONC uses in its own operations, the organization operates a platform that allows companies to test and demonstrate their technologies. With camera systems and sensors delivering real-time data, companies can show potential funders or clients the impact of their work.

Building Drones and Sleds

Based in Nanaimo, Shift Coastal Technologies is a coastal resource management company. Among its technologies is an incident reconnaissance and intelligence drone used to detect oil spills, collect samples of surface water, detect polluting bilge water and support search and rescue efforts.

On the water, Shift has also developed an uncrewed surface vessel called the OceanSled. The sled can be deployed alongside a boom to help contain small-scale spills or use an attachable apparatus to help search and rescue teams extract a victim.

The applications for both technologies, combined with Shift’s cloud-based dashboard, have been adopted by First Nations, industry and government. Shift CEO James Spencer says that the company is finalizing a project with the Canadian Coast Guard that will allow it to better monitor oil spills and manage its response.

Speaking to the reality of the Island’s ocean tech industry, Spencer says, “It’s definitely not the easiest place to operate a business in the technology space. Especially one looking to manufacture and market to the global maritime sector.”

A Big Umbrella for Ocean Tech

Addressing the challenges faced by Vancouver Island entrepreneurs is exactly what the Centre for Ocean Applied Sustainable Technologies has set out to do.

The idea for COAST emerged when representatives from local municipalities, businesses and associations met to discuss the Greater Victoria economy and which sectors were most likely to succeed post-pandemic. Among them was the blue economy. Many meetings later, COAST was incorporated and in 2021 the innovation centre was brought under the wing of the South Island Prosperity Partnership.

“Our focus is all about economic development. We want to set up an environment in which companies can grow and thrive in this sector and in this region,” says COAST executive director Jason Goldsworthy.

In order to help entrepreneurs overcome barriers to success, COAST is centred on four pillars: outreach, entrepreneurial support, pathways to talent and co-working facilities.

Goldsworthy says that for the last 12 to 18 months the organization, still in its infancy, has been focused primarily on its first pillar: outreach, engagement and building a local blue economy network.

MarineLabs’ Beatty echoes the need for a stronger blue economy community on Vancouver Island. “If you took a snapshot of what the ocean tech scene looked like five years ago, it was a lot of silos,” he says. “It was a lot of people who were individually developing stuff and trying to find markets on their own.”

Tradition Meets Tech

The Association of British Columbia Marine Industries has played a key role in the founding of COAST and is another organization working to break down silos. ABCMI represents B.C.’s industrial marine sector which, including ocean-tech companies, consists of nearly 1,100 companies and 34,200 jobs, and generates some $7.2 billion.

The long list of the association’s core activities includes workforce and skills development, enabling business opportunities, developing supply chains and promoting B.C. exports.

Through the work of organizations like ABCMI and COAST, and through entrepreneurs themselves, there’s a growing sense of collaboration among the Island’s ocean tech community. It turns out that what’s good for the ocean may also be good for business.