If we want homes, ships, pipelines, cars or the roads they travel on, we need people to build them. We need pipefitters and construction workers, plumbers and electricians, welders and stonemasons. We also need chefs, designers and hairstylists. We need the trades.

The trades refer to skilled hands-on labour professions that typically require specialized training and education, often including apprenticeships. In many areas, qualified trainees are eligible for Red Seal certification, a Canadian standard of excellence that allows certified tradespersons to work across the country.

“People in the trades are highly skilled. A trades career requires a lot of knowledge,” says Joy Wickens, the dean’s assistant at Camosun College’s school of trades, industry and professional studies. “We should encourage their celebration.”

Yet skilled trades have often been overlooked as a career path, despite the level of expertise they require. That’s changing now — after all, trades jobs tend to pay well and are largely AI-proof — and demand for training is on the rise.

According to SkilledTradesBC, there are 90 trades training programs in B.C., with 49 of them leading to Red Seal accreditation. But that, many say, isn’t enough to meet demand. And although both the federal and provincial governments have emphasized the importance of the trades and promised financial help, it’s lagging behind the actual need. At Camosun, for instance, certain trades programs are underfunded by about 30 per cent. “We can’t get the funding for the programs we want,” Wickens says.

According to SkilledTradesBC, there are 90 trades training programs in B.C., with 49 of them leading to Red Seal accreditation. But that, many say, isn’t enough to meet demand. And although both the federal and provincial governments have emphasized the importance of the trades and promised financial help, it’s lagging behind the actual need. At Camosun, for instance, certain trades programs are underfunded by about 30 per cent. “We can’t get the funding for the programs we want,” Wickens says.

“Tradespeople work with their minds and their hands,” says Shelley McIvor, managing director at Quadrant Marine Institute in Sidney. “Trades are underappreciated for how critical they are.”

Here are three very different schools in Greater Victoria that are helping train the next generation of tradespeople.

MARINE

Quadrant Marine Institute

McIvor once spent her days in a laboratory as an analytical chemist. About a decade ago, she ditched the lab coat for work boots as managing director at Quadrant Marine Institute in Sidney. As her lifestyle changed, so did her career aspirations.

McIvor lived on a boat for several years and traversed the Panama Canal. She knows her way around ocean-going vessels, so her knowledge was a great fit for QMI. “This is my happy place,” she says.

McIvor’s happy place was formed 30 years ago by marine industry owners and professionals who were facing difficulty finding skilled workers. “Quadrant decided to start providing courses to cover the whole boat, from bow to stern, all the technical aspects in a vessel,” McIvor says. QMI’s tagline is “We Float Boats,” but QMI also launches careers.

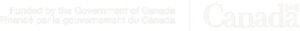

There’s no shortage of pleasure cruisers, light commercial vessels or fishing charter boats that need servicing. Within a five-kilometre radius of Sidney’s Canoe Cove Marina, McIvor estimates there are 5,000 such vessels, about one-tenth of them at Canoe Cove, where QMI is based and where teaching happens. “You never stop learning in the industry. Every day is different. Every boat is different. Boats are incredibly customizable,” McIvor says.

QMI’s dive into training happened on the fly, and since 1996 there’s been a constant evolution of the program, partly in response to ever-changing provincial training standards and marine demands. By 1998, QMI’s training program was recognized by the province and soon after its marine service technician (MST) credential came into being.

QMI provides training in Sidney and Vancouver and has expanded to Nanaimo. The instructors are people actively working in the marine industries. “Every one of them teaches from their speciality,” says McIvor. Programs draw apprentices from across Canada who funnel into three streams.

The first, marine service pre-employment, is a six- to eight-week course, for ages 16 to 29, where students start in the classroom and progress to work experience.

The second is a four-year apprenticeship program where students finish with a MST certification. It is the most popular of the options, McIvor says. Sponsored by their employer, students continue to work at their marine jobs while building their skills.

“They learn the whole scope of the boat,” McIvor says. Safety, design, installations, composites, wood, metals, paint, rigging, electronics and mathematics are covered. “Some apprentices learn one area and then move on to another,” McIvor says of the lifetime process to master MST.

The third stream is manager training. Groomed to be a project manager, students commit to online learning, workshops, months of actual managing and a review.

Graduates are not Red Seals; instead, MST is considered a qualifications trade, bestowing a journeyperson ticket. The certificate of qualification proves that an individual is qualified to work in the relevant trade occupation in Canada and has passed the licensing exam.

McIvor says there are always jobs available in the marine industries, where entry-level workers earn approximately

$25 per hour, a journeyperson can earn $35 per hour and up, reaching $50 or more per hour for a lead hand or supervisor.

McIvor touts the community-based feeling evident in QMI’s philosophy. Having close-at-hand peers who can assist is valuable given that some of the vessels being repaired or maintained could be $10-million yachts or Coast Guard ships.

“These are not careers that AI will be able to replace,” McIvor says. “You have to be physically able to take things apart and put them back together.” When human lives are involved, onboard systems must be structurally sound and safe. “Technology helps, but will not replace a person.”

CULINARY

Camosun College

For many students interested in a career — often, a second career — in the trades, be it culinary or carpentry, horticulture or heavy mechanical, plumbing or electrical, their path takes them to Camosun College and the school of trades, industry and professional studies.

Emma Hunsche gave up a seven-year, physically demanding job as a route setter (a person who designs and creates paths on rock-climbing walls, primarily in indoor climbing settings) to continue her learning quest in the culinary arts.

“After climbing, food was my next biggest passion,” says Hunsche, who grew up near Edmonton and was influenced by her oma’s German cooking and a mother who experimented with a myriad of cuisines. “I was ready to reinvest in my education and I heard really great things about the culinary arts program.”

Hunsche isn’t sure where she will work once her training finishes, but she’s considering pastry cookery or working at a local farm-to-table enterprise. “It’s exciting not to know where I’ll end up,” she says. But she does know that possessing a trade’s skill is incredibly rewarding. “You get better and better. You keep learning your whole career.” Demand for culinary training is strong, says David Lang, chair of culinary arts at Camosun, where he has been training cooks for over eight years. Just recently, some 28 students applied for the 18 spots in Level 1 of the professional cook certificate program.

In Lang’s kitchen, there is a range of ages, genders and origin stories, but for all of them, the focus is on developing skills and elevating quality cuisine in a community environment. “If you can make a good grilled octopus, you can make a burger,” Lang says. And, he adds, as with all the trades, the tools are important: “We don’t use drills or hammers. We use knives and whisks.”

In Lang’s kitchen, there is a range of ages, genders and origin stories, but for all of them, the focus is on developing skills and elevating quality cuisine in a community environment. “If you can make a good grilled octopus, you can make a burger,” Lang says. And, he adds, as with all the trades, the tools are important: “We don’t use drills or hammers. We use knives and whisks.”

Graduates have plenty of options. They can work in a restaurant, of course, but they can also work as bakers or private chefs, open a food truck or a ghost kitchen, become a caterer or work on a cruise ship. And, like many other trades, the culinary arts may well be one of the few careers that are resistant to artificial intelligence. As Lang says, “It’s easy to make a good soup. It’s hard to make a great soup.”

Like most Camosun trades training, culinary arts offers two paths: foundation or apprenticeship programs. The foundation stream is pre-employment professional cook training that gives the student basic, practical skills at two levels after 28 weeks. The apprenticeship program offers six-week professional cook training for three levels; those who complete Level 3 receive their Red Seal.

ELECTRICAL

Aside from its culinary arts program, Camosun also offers training in a wide range of other trades. But in some areas teachers are juggling numbers and reluctantly squelching dreams. There just isn’t enough money to add enough training spaces or to upgrade equipment, even though there are wait-lists for programs in oversubscribed areas such as electrical, sheet metal, heavy mechanical and automotive service.

“Over 10 years, there hasn’t been increased funding for apprenticeship training,” says Kyle Broad, Camosun’s chair of motor vehicle and metal trades. “There’s no shortage of students. In fact, there’s wait-lists,” says Wickens.

“Over 10 years, there hasn’t been increased funding for apprenticeship training,” says Kyle Broad, Camosun’s chair of motor vehicle and metal trades. “There’s no shortage of students. In fact, there’s wait-lists,” says Wickens.

The high demand for Levels 3 and 4 training would give graduates their Red Seal designation, but wait-lists are long and there’s no money to add more seats. Adding to the shortfall is the much-diminished number of international students, whose high tuition fees helped fund programs for training women and Indigenous students in the trades. Those offerings have been suspended.

During their election campaigns, the parties that would form both the provincial and federal governments promised new funding for trades apprenticeships, but that money has yet to appear. Meanwhile, although the Canada Apprentice Loan program offers interest-free loans to help registered apprentices with the cost of their training, a pair of federal apprenticeship grants ended on March 31. And while Camosun’s fundraising foundation is active, it takes money to find money, Wickens says, adding, “Every gift comes with a cost.” Often that cost is the long-term maintenance of a one-time project, which inevitably falls on the college.

So Broad continues to wait. He notes, though, that all levels of government are also making promises about building more housing and other infrastructure. “We won’t be able to meet those objectives if we don’t get apprentices through the system,” Broad cautions. “If students have to wait two or three years, they’ll do something else.”

DESIGN

Pacific Design Academy

At downtown Victoria’s Pacific Design Academy (PDA), upgrades to the premises and equipment are vital for the privately operated institution. Graphic media design, fashion design, interior design, architectural building technology, app and web development, and motion-picture production all require the latest equipment.

“We are a college really interested in students’ career goals. We are very hands on,” says Mary-Claire Ukah, PDA’s registrar and communications contact.

At PDA, class sizes don’t exceed 18 students. Instructors are industry professionals who bring their experience into the classroom. “They focus on skills that lead to real jobs. They are passionate,” Ukah says.

But quality comes with a price. Tuition runs about $13,000 to $16,000 per year and most programs span two years. (Comparatively, one year of tuition at the University of Victoria is roughly $12,000.) Shorter terms exist for those wanting professional design certificates or enrolling in evening design workshops (learning a new skill).

Ukah adds that not everyone wants to complete a four-year university degree. PDA’s creative aspects hold appeal for high school graduates and dissatisfied university students. “We have a lot of students who got four-year university degrees and then come to PDA,” she says. Most students are in the 18-to-40 age range and most are from Canada. Fashion design is the most popular full-time diploma program, followed by interior design. Pay rates for graduates are project specific, with graphic design being one field where wages can be high. New interior designers start at around $20 per hour, but Ukah says that wages can soon reach $30 per hour.

Katie Csuka finished her two-year interior design program in June and had already secured a job several months before she completed the course. “It’s an education that sets you apart from other careers,” says Csuka. The broad scope of the course teaches students how to create photorealistic renderings or 3D computer models, draft construction drawings and advise on colour/finishes/lighting/furnishings, all while meeting clients’ needs.

Csuka, who grew up near Calgary, later moved to Victoria to attend UVic as a psychology student. But after two years she realized it wasn’t her calling. “I wanted to get right into my career.” Another factor playing a role in her decision was that a lot of psychology BA graduates have a very difficult time getting into a master’s program. “Some students go to school for four years and don’t use the degree, especially psychology,” Csuka says.

Not afraid to classify interior design as a trade, she has embraced the many hats she dons in her new career, from discovering clients’ wants to using Lumion to create realistic photos to drafting construction plans. “And there’s fun stuff, like colour palettes,” she says.

Answering the Call

With headlines, industry reports and expert analysis all pointing to an urgent need for tradespeople, the full program wait-lists show that people are ready to roll up their sleeves and fill the gaps. “In so many trades you create with your hands,” says chef-in-training Hunsche. “If your hands are dirty, you’re creating something.”