Back in the 1970s, my mother was unable to get a credit card without my father’s approval despite the fact that she was a tenured professor at the University of Victoria. Today, half a century later, against every demonstration of equal competence and business acumen when measured against their male counterparts, women are still at a significant disadvantage when it comes to securing funds for their businesses.

Fundamentally, and academically, we know that women are capable of running stable and high-growth businesses. Rare it would be for someone to publicly dispute that (unless you’re that guy screaming into his microphone to his 200 listeners). However, research shows that women have a significantly harder time securing capital than men. A Harvard Business Review study dove deep into this issue, finding that investors of any gender are more likely to invest in a woman’s business if she already has a male investor — and they are significantly less likely to invest if her sole source of funding comes from other women. When people see that a woman-led business has a male investor, they attribute that investment to competence. On the flip side, when people see that she has a female investor, they attribute that capital raise to her gender. As such, potential follow-on investors are likely to view the woman as less competent if she has a leading female investor.

In this respect, women still need a man to sign for their credit card.

Winning Versus Not Losing

Tessa McLoughlin, founder and CEO of KWENCH, is eager to grow her thriving business, which is one of the most vibrant and well-attended co-working clubs in the city. But she has had an uphill battle in her fundraising endeavours. “I wanted to have an all-female cap table and that definitely made the already-challenging task of finding investors harder. Women investors took significantly longer to commit, and they typically came in under the minimum ask. Of course, there can be many reasons for this, and some are systemic,” says McLoughlin.

These biases are not limited to men. They extend to people of all backgrounds. At the end of the day, according to the research, having a strong male lead as an investor makes it easier for people to come to the table and for them to take decisive actions.

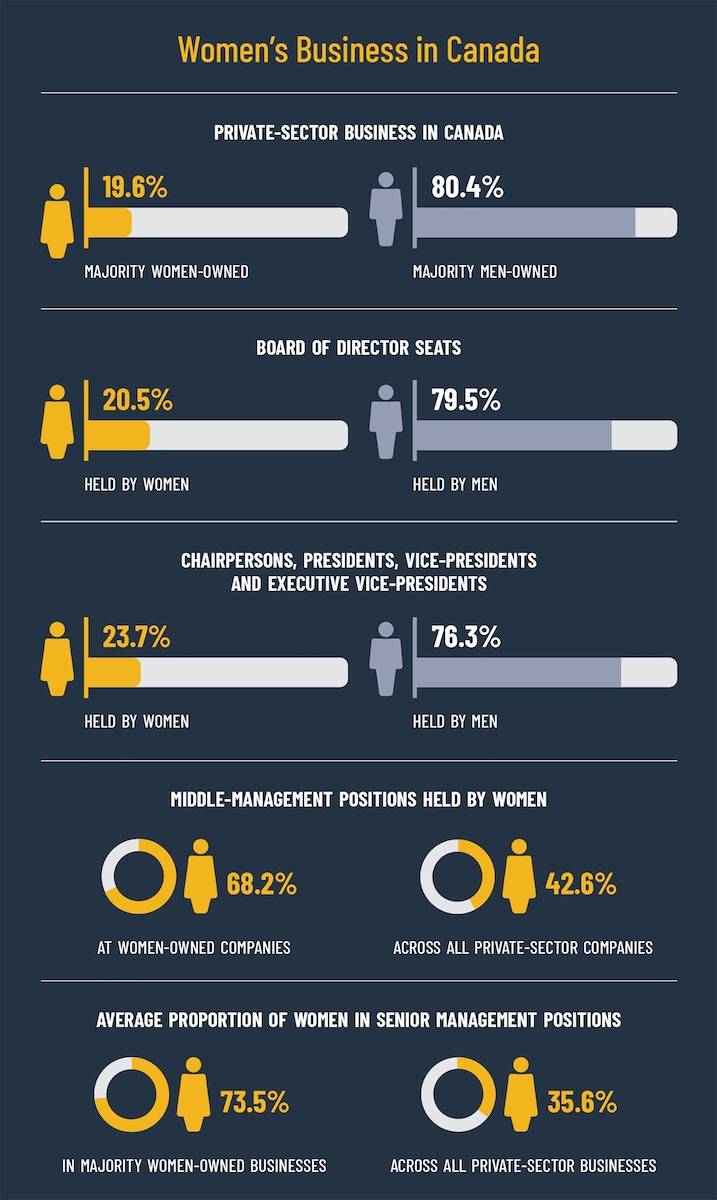

This finding only scratches the surface of the challenges that female business owners face. For one thing, it isn’t just who is already at the table, but who is running the company. Approximately 20 per cent of businesses in Canada are women-owned, but their businesses receive only around two per cent of available investing dollars. That could be due to a variety of factors, but with numbers like that it is evident that at least some of them are due to entrenched gender perceptions and biases.

“We need to see more women investing in other women, as we are often building companies that address shared pain points and innovations that might not be evident to men.”

Tessa McLoughlin, founder and CEO of KWENCH

Further research by Scientific American revealed it is the “quality of interaction” that is driving the disproportionality. Men are more likely to be viewed as conquerors of commerce (think: renowned giants of the tech industry) while women are seen as running small or medium-size lifestyle businesses with little recognition. As such, men tend to be asked questions about how they are going to win; women are more likely to be asked how they are going to avoid losing. These stereotypes, however unconscious they may be, frame investor interactions and create biased approaches when considering both the founder and the quality of the investment.

“I often have to front-load my pitch so that investors don’t get distracted by their concern over risk [and] so they can really focus on the vision that I am painting,” says Nicole Smith, founder and CEO of Flytographer. “So, from the start, I talk about how we are going to mitigate risk so I can get to the part that everyone wants to hear: How are we going to grow?” Smith is definitely on the right track here as the Scientific American study further revealed that those who were asked “preventative questions” and responded with “preventative answers” received significantly smaller cheques, approximately $563,000 on average, than those who shifted quickly and responded with “promotion-focused answers” and raised on average in excess of $7 million.

Education Is Just a Start

There are any number of programs that aim to close this gap, but when looked at broadly they tend to fall short and pull focus away from the fundamental problem.

Accelerators and mentorship programs that function through the lens of DEI (diversity, equity and inclusion) initiatives can be gruelling, time consuming and often come with “in-kind” prizes with limited cash funding that make grand prizes seem more impactful than they actually are.

“The reality is that most of the female founders I’m surrounded by don’t need more education or mentorship — they really just need funding.”

Linda Biggs, co-founder and CEO of joni

Linda Biggs, co-founder and CEO of joni, has been in raise mode for a while, trying to get her line of inclusive and sustainable menstrual period care funded for growth. Not only is she running a woman-led business, but she is in a category of products that have typically been relegated to discreet discussions amongst women in the bathroom. As a female founder, Biggs has completed over five accelerators in the past 12 months, and she has some thoughts on why the system is not really working. “Most accelerators focus on education and mentorship in order to get to the funding, many times requiring six-plus hours a week attending training, talks or some kind of mentorship session,” she says. “The reality is that most of the female founders I’m surrounded by don’t need more education or mentorship, they really just need funding.”

Sage Lacerte, director of inclusion for Boann Social Impact fund, which manages over $145 million, is often on the other side of the table, but has similar challenges in operating in the male-dominated world of investing and fund management. “My experience as an investor and as someone who is visibly Indigenous, a woman and a younger person — there is an immediate narrative that I am inexperienced and could use mentorship or that I need advice,” says Lacerte. “It happens in almost every single room.”

Significant Hurdles

Mentorship, DEI initiatives and accelerators are useful in moderation, but should not be leveraged as the solution to the huge gap in funding for women. Every female entrepreneur out there knows that women are vastly underfunded. We’ve all seen the data and sighed heavily for the 300th time after a gruelling round of fundraising that always feels like it fell short or was much harder than it needed to be and said, “We need more women to invest in women.” The concept, on its face, feels like not only a viable solution but an empowering one: “If they won’t invest in us, we’ll invest in ourselves.” And notionally, it isn’t wrong.

“We need to see more women investing in other women, as we are often building companies that address shared pain points and innovations that might not be evident to men,” says Kwench’s McLoughlin. And she’s right. Deeply held biases not only prevent women from taking a warmed seat at the table, they also cause the investment community to miss out on potentially innovative and disruptive companies. Female investors could benefit from these overlooked opportunities in women-led companies through their common perspectives.

That said, there are some significant hurdles to get through before that can become possible.

Firstly, women hold vastly less capital than men. Globally, women hold 30 per cent of all wealth controlled by individuals and families, with men, as individuals, holding on average 30 per cent more net wealth than women, according to the 2024 Quebec study by the Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique.

“Talking about investing has not been a part of the traditional women’s network and not something they have been invited to participate in.”

Stephanie Andrew, the national director and co-founder of Women’s Equity Lab

Further, women exhibit a notable difference in their level of confidence when it comes to making investments. According to the U.S.-based Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, only 34 per cent of women, compared to 50 per cent of men, feel confident in making investing decisions. And only eight per cent of women demonstrate high investment knowledge, compared to 21 per cent of men surveyed.

Compounding all of these statistics is the finding that 91 per cent of women in a 2017 Fidelity Investment Canada survey think men make better investors. Ouch.

That is not to say there is not an incredibly strong movement of women-led investment funds and angels that look beyond these biases and invest with acumen that rivals traditional funds, but there are simply not enough to address the shortfall in investment in women-led businesses.

Stephanie Andrew, the national director, managing partner and co-founder of Women’s Equity Lab, which manages a growing portfolio of over 400 female investors, confirms that women are not investing enough to fill the funding gap in women-led businesses. Not yet, anyway. “One of the primary challenges women face is that they have historically not been a part of the conversation when it comes to investing,” she says. “Talking about investing has not been a part of the traditional women’s network and not something they have been invited to participate in.”

Connections and Divides

A Wharton School of Business study on gender-driven investment noted that “similarity breeds connection,” what is known as the homophily principle. Since the majority of investors are men, they are more eager to form connections with male entrepreneurs and investors, forming networks that women have difficulty accessing.

When taking into account the small pool of funds that women comparatively control overall, the newness of women simply having access to and control over their own assets (roughly 50 years) and the odds that seemingly never seem to stop stacking up, it feels challenging to put the weight of this problem squarely on the shoulders of women alone.

Women are known to create better returns than their male counterparts by about 40 points or 0.4 per cent and produce less reduced returns per year as a direct result of their more cautious investing practices. But despite that, a Harvard Business Review study that looked at more than 2,000 venture-backed firms in the U.S. found that female-led firms whose funding came exclusively from women were significantly less likely to obtain subsequent rounds of funding.

And yet women are expected to prioritize funding women-led businesses that, for all intents and purposes, the wider investment community devalues if a woman is the lead investor.

“We don’t need more advice, we need men to crash down doors for us.”

Jane Desrochers, local angel investor

The fact is there are still very few female investors with the means, capacity, resources and access to fully invest in other female-led ventures. Female investors tend to be concentrated in funds that focus on early-stage, higher-risk investments and control much smaller sums of capital.

The data, time and time again, clearly and consistently show that women-led businesses perform just as well as, if not better than, those of their male counterparts. Yet the very fact that there is such a huge gap in funding leads researchers to study the gender-driven deficits. This then leads to data on the scarcity of investment in women-led businesses, creating manufactured risk and biases that may prevent not only men, who hold 95 per cent of the positions in venture capital, but also women from investing in women.

“It’s frustrating that the scarcity of funding for women-led businesses is trying to be solved with more scarcity models — having women compete against each other for a small pool of money. We need to move past that,” says Biggs.

It’s the Money, Honey

The bottom line here is the belief system has to change.

Generally, we think of investors as shrewd, calculated and data driven, but evidence shows they are often impulsive and emotional, factors that invite the kind of biases that prevent women from breaking through in a meaningful way.

The solution here is twofold in the eyes of women on both sides of the table: First, the change comes with more radical decision-making practices that acknowledge and push past these biases. Jane Desrochers, a local angel investor, says, “We don’t need more advice, we need men to crash down doors for us.” Essentially, men need to enter the chat here. Not to hold the pen as cheques are signed, but to make room for more diverse investing practices to take up space. Conversations need to shift toward the practicality and profitability that come with investing in women. Women require strong, consistent and power-holding advocates at the table that includes a warmed seat beside them.

The second solution could not be more straightforward. In the immortal words of Jenny Slate’s character Mona-Lisa Saperstein from the TV show Parks and Recreation: “MONEY PLEASE!!”

Instead of more studies, accelerators, mentorship, advice and DEI initiatives — or more think pieces like this one, for that matter — women need dollars. Period.